Incremental Innovation: Too Much of ‘Too Little’ in MedTech

At a recent panel, a senior clinician asked a room of device and pharmaceutical leaders a simple question.

“Can you not give us all the innovation at once instead of piecemeal. Why do you expect me to switch or upgrade for minor improvements, a knob here, a software tweak there, slightly more power.”

The question drew laughter, but it lingered in my mind. I have worked on both sides of this debate — as a clinician who uses the technology and as a business leader who shapes it — and I understood his frustration.

It also brought to mind Apple’s September 2025 launch, criticised for its “new colour, faster chip” line up. The event prompted the same question: why upgrade if nothing important has changed. MedTech, for all its regulation and clinical gravity, is not immune to this pattern. We, too, risk mistaking movement for progress.

The clinician’s challenge captures an uncomfortable truth. Much of MedTech’s progress arrives through small refinements rather than big steps. Why? Must it be so? Is there value in it?

1. Why small steps dominate

Incremental innovation requires less investment and carries less risk. The United States Food and Drug Administration clears about ninety five percent of new devices through the 510k pathway, which relies on showing that a new product is substantially equivalent to one already on the market. Only a small fraction of devices go through the more demanding pre market approval process [1].

The cost gap is equally stark. Developing a 510k device costs about thirty million dollars on average. A novel product that requires pre market approval costs roughly ninety million [2]. Most 510k submissions do not need new clinical trials [3]. For executives managing quarterly performance, the preference is obvious. Small steps provide reliable returns. Yet each small step also erodes excitement. After Apple’s launch, consumers asked what was new. Clinicians ask the same question when offered a slightly improved version of the same tool.

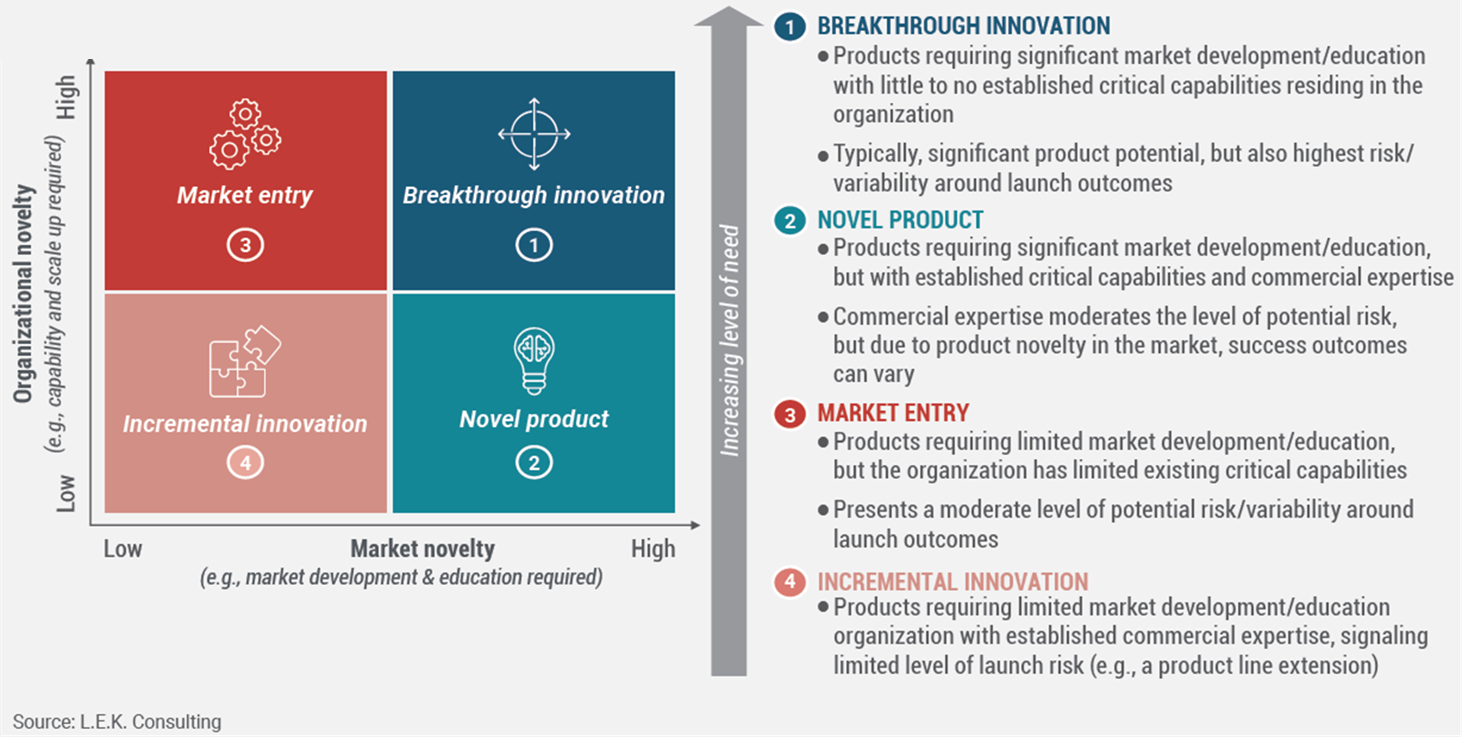

Figure 1: Investment and risk profile by innovation type

Incremental innovation sits at the low investment and low risk end of the spectrum. Breakthrough innovation requires greater resources, longer development, and carries far more uncertainty.

Source: L.E.K. Consulting, 2025

2. Evidence of the pattern

Across MedTech, most new products are variations of what already exists. Devices cleared through the 510k pathway account for roughly 95 percent of annual FDA approvals, compared with 2–5 percent through PMA. Product lifecycles are now as short as two years before an improved model appears [4].

Even genuine breakthroughs tend to be followed by a cascade of minor revisions. A study of cardiac implantable devices found seventy seven original pre market approvals and more than five thousand supplemental modifications over time, most cleared without new clinical evidence [5]. One leap becomes fifty follow on steps.

Figure 2: Supplemental Approvals Following Breakthrough Devices

Each original PMA approval for cardiac implantable devices is typically followed by about 50 supplemental approvals, most without new clinical data.

Source: Rome and Kramer, JAMA (2014).

A 2023 McKinsey analysis showed that incremental innovation now accounts for a disproportionate share of company portfolios, while measurable clinical benefit remains limited [6]. Devices described as “major upgrades” often face price resistance from hospital buyers. Meanwhile, companies that delivered genuine breakthroughs between 2017 and 2023 achieved shareholder returns twice as high as peers focused mainly on incremental projects [7].

The logic of incrementalism makes sense in the short term. It protects share and manages risk. But it also narrows ambition and invites scepticism from the very clinicians whose confidence the industry depends on.

3. The structural forces behind incrementalism

The pattern is reinforced by four system level realities.

First, the pipeline of new ideas is thinner. Large device companies now depend heavily on start ups and universities for early breakthroughs, but venture funding for young MedTech firms has declined and patent activity has plateaued [8]. Investment increasingly goes into extending proven technologies rather than exploring untested ground.

Second, the regulatory and cost barriers to genuine novelty are high. Pre market approvals require longer evidence generation and deeper clinical trials. In Europe, new regulatory frameworks have raised compliance costs further [9]. It is no surprise that companies choose faster, cheaper routes when possible.

Third, adoption moves slowly. Even when regulators approve a breakthrough, it can take a decade or more for broad clinical use. Reimbursement lags add further delay. A Stanford Biodesign survey found that Medicare coding and coverage for novel devices took between two and five years after approval [10].

Finally, commercial habits reinforce the cycle. Regular product refreshes give sales teams something new to promote and investors a sense of progress. Over time, the rhythm of constant updates becomes institutionalised.

Incrementalism, then, is not always a strategic choice. It is often the outcome of the system itself.

4. APAC and Singapore: from constraint to catalyst

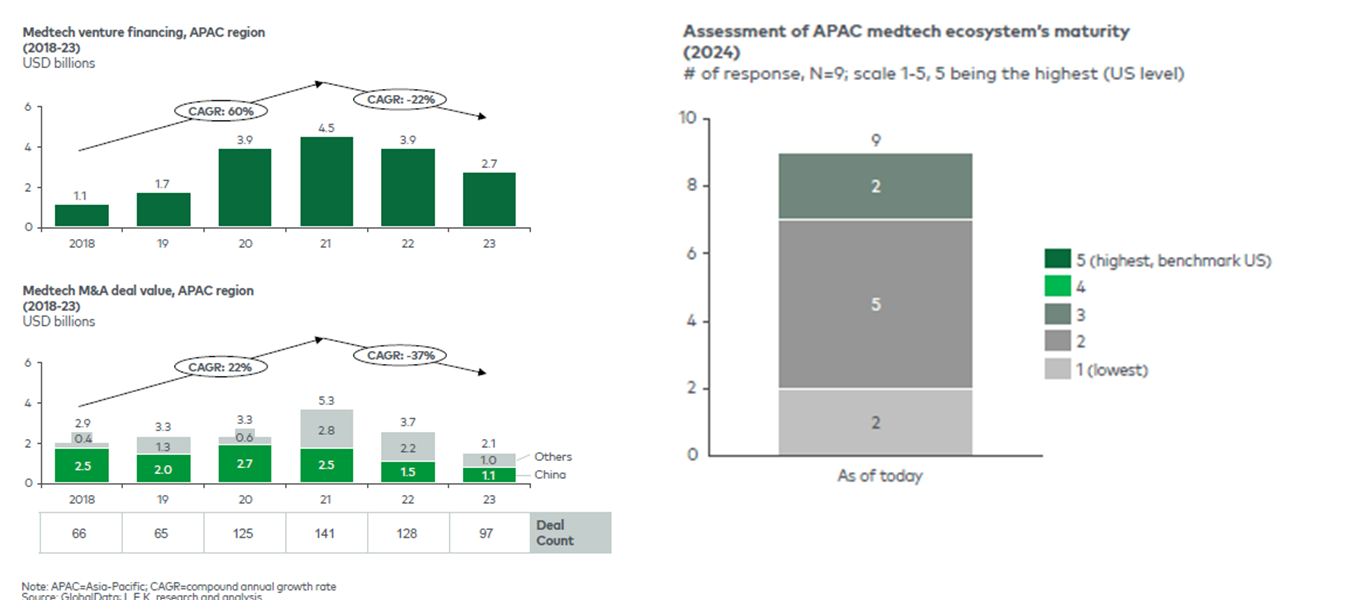

These dynamics are visible in sharper relief across Asia Pacific. Venture funding in MedTech declined twenty two percent after its 2021 peak, and merger activity fell thirty seven percent [11]. Many innovators operate in fragmented regulatory environments and uneven reimbursement systems. Small, stepwise innovation often feels like the only viable option.

Figure 3: APAC MedTech Investment Trends (2018–2023)

Venture financing fell 22 percent and M&A value 37 percent since 2021, illustrating the funding pressure that shapes innovation strategy across the region.

Source: APACMed and L.E.K. Consulting (2024).

Yet the same constraints that limit ambition can also create opportunity. The diversity of healthcare systems, resource limits, and fast growing demand across the region invite a different kind of innovation — solutions that are practical, affordable, and digital. Portable imaging, AI diagnostics, and connected monitoring are expanding quickly in Southeast Asia precisely because legacy systems are lighter. Here, what looks incremental in a Western context can be transformational locally.

Singapore illustrates how this balance might work. The country delivers world class outcomes while spending around four percent of GDP on healthcare [12]. Its ecosystem now includes more than thirty biomedical research centres and regional facilities for global firms such as BD, Medtronic, Siemens Healthineers and ResMed, alongside emerging local ventures supported by the HealthTech Hub and Diagnostics Development Hub [12].

Under the RIE 2025 and RIE 2030 plans, Singapore continues to invest heavily in precision medicine, digital health, and AI infrastructure [13]. The ambition is to act as both a base for frontier research and a proving ground for incremental development suited to Asia Pacific markets.

Figure 4: Singapore’s RIE and Ecosystem Enablers

Growth in value added, employment, and research partnerships from RIE 2015 to RIE 2025 demonstrates Singapore’s progression from manufacturing hub to regional innovation node.

Source: L.E.K. Consulting (2025)

A company designing a surgical robot, for instance, could refine software for regional hospitals while developing next generation capabilities for global use. In one ecosystem, both modes of innovation can coexist.

Singapore’s strength lies in compressing the time between idea, validation, and adoption. Clear regulation, diverse data, and close links between academia, industry, and government make it a working model of how a system can support both breakthrough and incremental progress

5. From listening to leading: making each step count

The difference between progress and motion often lies in how well companies listen. Understanding the customer is not a milestone before launch; it is a constant discipline. Markets evolve faster than internal roadmaps. Insights gathered years before approval may already be stale when the product reaches market.

Too many teams rely on anecdote from a few advocates rather than evidence from a broad user base. Real market sensing means continuous dialogue — combining research, data, and field experience to understand what customers truly value and when they are willing to change.

When companies keep close to their users, they know when a new feature adds value and when it can wait. If an upgrade does not improve outcomes or solve a real problem, postponing it may build more trust than pushing it out on schedule. Launching low value updates risks the same fatigue that plagues consumer technology.

The principle is simple. Make small steps meaningful. Invest in the refinements that improve safety, integration, or workflow. Use software updates to extend performance without forcing constant hardware replacement. Allocate resources deliberately between incremental work that sustains the base, adjacent innovation that expands capability, and exploratory projects that open new frontiers.

Adoption planning should start early. Working with regulators, payers, and clinicians during development shortens the lag between approval and access. Modern commercial models — such as subscription or service agreements that keep systems current — can also reduce the pressure to release superficial upgrades just to generate revenue.

When incrementalism is guided by disciplined listening and long term intent, it becomes a foundation for trust rather than fatigue. It keeps the organisation close to the market while freeing resources for the occasional leap — the rare advance that changes the field and reminds us why innovation matters.

Most advances in MedTech arrive quietly: a lighter instrument, a clearer image, a safer procedure. These changes matter. They make care better day by day. But too many releases with too little difference can dull belief in progress itself. The clinician on that panel was not asking for perfection. He was asking for purpose.

Asia Pacific, and Singapore in particular, show what that purpose might look like. With the right support, ecosystems can nurture both steady improvement and bold experimentation. The task for MedTech leaders everywhere is to make each new product, whether modest or transformative, earn its place by improving patient outcomes or clinician experience in a measurable way.

References

[1] United States Food and Drug Administration, 510k programme data and reports.

[2] Makower J and colleagues, survey of device development costs.

[3] FDA, Guidance on Use of Clinical Data in 510k Submissions, 2024.

[4] MedTech Europe, Innovation in Medical Technologies, 2020.

[5] Rome B and Kramer D, FDA Approval of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices, JAMA, 2014.

[6] McKinsey & Company, MedTech Pulse: Thriving in the Next Decade, 2023.

[7] McKinsey & Company, Value Creation Priorities in MedTech, 2023.

[8] Zapyrus, MedTech in Numbers: 2024 Report.

[9] MedTech Europe, MDR Impact Assessment, 2021.

[10] Stanford Biodesign and JAMA Health Forum, analyses of coding and coverage delays, 2022–23.

[11] APACMed and L.E.K. Consulting, Fueling the APAC MedTech Innovation Engine, 2024.

[12] L.E.K. Consulting, Unlocking Growth: Singapore’s Role in Advancing MedTech Innovation, 2025.

[13] National Research Foundation Singapore, RIE 2025 and RIE 2030 Plans, 2025.

These views are personal and do not reflect those of my firm, employer, or any specific client